Publications > Scream City > Scream City Issue #2 > Andy McCluskey by John Cooper

Andy McCluskey

by John Cooper

by John Cooper

Andy McCluskey of OMD tells Scream City all about the early days on Factory, the plans for a new album & live shows and the art of going "Rococo Bonkers".

JC - In the new LTM documentary, 'Shadowplayers', Lindsay Reade says that the reason why 'Electricity' came out is that Tony Wilson did it for her because she liked it so much.

AM - Well that kinda corroborates the story I'd heard from other places which was that after we played at Eric's, the people who ran Eric's, Roger Eagle and Pete Fulwell (we just played Eric's as a one-off gig, it was a dare, to go on stage and do it with a tape recorder and we called ourselves the most preposterous name we could think of because it didn't really matter), said well listen y'know Joy Division have come here and we've got a reciprocal relationship with these guys in Manchester who have a night so why don't we send you over there.

So we said "well, we've done one gig, why don't we do two?"

And we played with Cabaret Voltaire at the Russell Club and we met Tony that night and I think subsequently, a week or two later, we were watching Granada Reports where he used to do the news, we saw The Human League on there and we were just being cheeky, we thought "well if The Human League can get on there...", we've met him, so we'll send him a tape of the recordings we'd done in our manager's garage of 'Electricity'.

And the story is that he didn't really get it, wasn't that impressed but left the cassette in the car and his wife liked it, and bent his ear about it – "what's that tape you've got in the car? That's bloody brilliant. Why don't you release that? Come on y'know, you're starting a record label!?".

So that kinda corroborates the story I had heard and I think Saville claims to have had some influence on the decision because he liked the idea that there was these two kids from Liverpool who were into Kraftwerk of all things, and who were doing their own version of Kraftwerk and he thought that was quite cool. So I think that maybe there was a bit of ganging up on Tony that forced his hand.

So yeah we went into Strawberry with Martin Hannett and he was fuckin' weird and scared the hell out of us! At one point he just climbed under the desk and went to sleep.

JC – I was gonna say, what was it like working with him?

AM – I remember thinking, cos we had a poxy little studio where we bounced from 2-track onto 4-track and back again. And we'd done this demo of 'Electricity' and we went into the studio which had 24-track recording and we had a bass drum which was basically a synth tuned down and he was putting it through all these graphics and we thought "this is taking bloody hours, what the hell's going on!?".

And then finally, the version of 'Electricity' and the version of 'Almost' that were done, we hated both of them. Recently somebody's unearthed something and was saying "what's this version?" and it's the Hannett version. As you might expect, it's very ambient and he's selected certain of the tracks to be more important than others and a completely different vision to the one we had.

So we said [to AHW] was, "we're really not happy about either of these mixes, he's kinda dismantled our songs and they don't sound anything like the way we saw them." And he said, well I've give you 'Electricity', I think maybe he's got a bit too clever, but what he's done to 'Almost' is magical, it's beautiful. 'Almost' was a very tight, kinda bouncy little organ-driven piece and he made it all this reverb and echo and much more sort of ethereal. And I have to say it took me months to actually get my head around it.

I didn't like either of them and we insisted that our version of 'Electricity' was released, the demo from the garage. But Tony insisted that Martin's version of 'Almost' was on cos he just said "no, he's transformed it". We got used to it after a while.

JC – There's 3 releases in all of 'Electricity' and the second release on Dindisc was 'Electricity' [Martin Hannett] and 'Almost' [Martin Hannett] and then it was released again with Paul Collister and OMD's remix of the Hannett version.

AM – I actually think that both versions that were released on Dindisc were the Hannett version but that they were both remixed. I think we got the tapes and we basically took what we recorded with Martin Hannett but we mixed it to sound more like our version which was a lot brighter, harder and more aggressive.

So I think both versions were based on the Hannett recordings but they were mixed by us to sound drier and more aggressive. I'm not sure, the Hannett version may have released somewhere down the line, I'll have to check.

JC – Which is the version on the reissue of the 'Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark' album?

AM – You know, that song has been in so many different versions and so many different releases that I'd have to put them all in a row and listen to them to have any chance of working out which one's which. It's always the case with your early songs.

They all get demoed and recorded so many times, particularly that one which was our "signature tune". I've completely lost track! I don't know if my mind's gone to mush with the passage of time, but I've lost track. I can probably go and try find all of the different versions. Paul Humphreys normally has a better of these sort of things. But that was it really for us on Factory because Tony saw Factory as being a stepping stone for us.

JC – But was there any point where anybody said "would you want to make another record with us?" Or was it always a given that you were going to move on?

AM – Well the funny thing was that Tony Wilson was the first one who actually said to us "well you guys are a pop group", which deeply offended us because we thought we were of experimental German influence.

He was like, "no, this is the new pop and you should be on Top of the Pops. We're just a new little label and we can't get you there. So what I see us doing is essentially that our release of 'Electricity' will be like a glorified demo".

And unbeknownst to us he sent out versions of 'Electricity' to all of the labels. Through that mail-out, Carol Wilson, who started Dindisc Records, received a copy and really liked it and eventually after seeing us a few times and coming to gigs, signed us.

And so, what happened was exactly what Tony suggested was going to happen. The Factory version of 'Electricity' would be a fishing tool to go and try and get major interested. I don't know to this day whether there was a deal done that Factory got any kind of cut or override on a second single. I seem to recall that there was some kind of "well, we'll have a percentage of the second…"

JC – A bit like selling a footballer?

AM – Yeah. So I think they may have got something of the sale of 'Red Frame, White Light', the second single or possibly they may have been cut in on the Dindisc release of 'Electricity'. The funny thing about 'Electricity' is that it goes down in the annals of musical history as OMD's first single and the seminal hook on which they hung their career. And everyone thinks it was a hit. But it wasn't. It got to 92 in the chart or something on one of its multiple releases.

JC – But it could've been if the right person had got wind of it…

AM – Well, I think one of the dilemmas we had was that by the time it was released on Dindisc, Gary Numan had come along and had hits. We supported Gary Numan on the tour he did in 1979. I think that the powers that be in radio, even though historically it was completely the wrong way round, saw OMD as jumping on Gary Numan's bandwagon and we were hacked off, y'know "who the fuckin' hell's this cockney bastard, pretending to do a robot thing!? We've been into this for friggin' years! If anyone's gonna have a hit it should be us or The Human League or somebody's who's been doing this for a while. Who's this Johnny Come Lately?".

Of course Numan's music was good and he treated us very well on his tour, but it was frustrating that certain people thought that we had copied him. Radio 1 wouldn't play us. I think it got to the point that it had been released so many times that once we had actually had hits that it was "no, we are not releasing 'Electricity' again!".

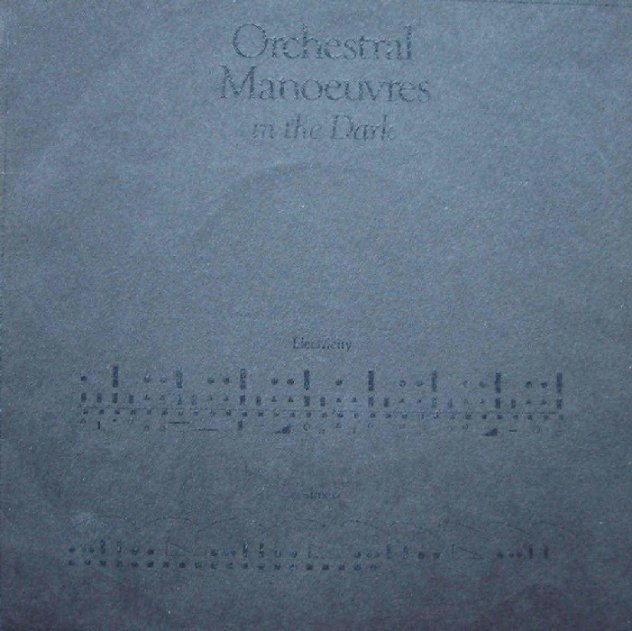

JC – Of course the sleeve of 'Electricity' saw the start of you working with Peter Saville. There's a good story about the production of the sleeve where a fire was caused due to the thermographic printing process used in the production.

AM – I don't know whether that was some kind of apocryphal urban myth but that's what I remember being told. I remember the first time we met Saville, because I had been to art college and fancied myself as something of a designer. I used to design the posters for ourselves around Liverpool when we first started playing.

The first time I met Peter it was just "oh alright, I'm not in the same ballpark here! He's got great ideas". I think right at the first meeting he suggested this black-on-black thermographed idea that he'd had. And it was, this is gonna be great but what were we actually going to thermograph onto this sleeve.

I think somehow it came up in conversation that he'd seen a non-manuscript way of writing music or something like that, which looked quite cool. We said, well actually that's the way we write music; we can't write manuscript. We write our beats in squares and we add dots and dashes. So we wrote out what 'Electricity' would look like in our kind of dots and dashes for the beats and things. So that's what the sleeve was: our version of how we write music.

I remember that myself, Paul Humphreys and Paul Collister, our manager at the time (who became our manager by default because he had the studio in the garage and the four-track Winston that we used in those days and he worked for Visionhire and he used to drive around in his Visionhire estate car). Me and Paul and Paul (I don't think Alan did it) went round to Palatine Road and we hand bagged every single one.

There was all the black sleeves and all the vinyl in white sleeves and every single version of that song, the 5000 that were made, one of either me, Paul Humphreys or Paul Collister has taken that out of the white bag and put it in the black bag, they were all hand bagged by the band and the management!

JC: And this is a traditional among early Factory releases, bands Like Joy Division, Durutti Column and Section 25 all of them being packed off to Factory to package records.

AM: Why employ labour when you've got band members lying around doing nothing! I think in hindsight it's a very nice story. It's literally hands on.

JC: Of course when you had left Factory and went on you still carried on your relationship with Peter Saville. Some people would say that the post-Factory OMD sleeves still look very Factory.

AM: I think you're right. Saville had a very distinctive style from seventy-eight to eighty-two which definitely leant on Constructivist. I mean I've just been down to Tate Modern today with my eldest daughter and I'm looking at Maholy-Nagy1 designs for posters and books and I actually pointed at one and said "If you take the orange off that, and you just leave it yellow & black is a Saville Factory poster.

He leant very heavily on certain influences and he'd be the first to admit it. He leant very heavily on Ben Kelly for the first album sleeve. It was typical Saville, he was doing the first album sleeve and the day before it had to be delivered he hadn't come up with anything and he was sitting there with Ben Kelly saying "What should I do?" and Ben Kelly said "Go down to Covent Garden to this shop where I designed the front door. That's your sleeve.

And Peter went down there to the shop and the door had a metal grid with these lozenges cut in it and Peter was like "Thank You!".

JC: There's a photo of it in Ben Kelly's book 'Plans and Elevations'.

[2019 note: the lozenge album sleeve was also used in the design of the stage set for OMD's tour in 1980. Peter Saville kindly supplied a photo of the original set design which was used in the centrespread of Scream City 2. This was wrongly attributed as being for the Dazzle Ships tour in the original paper version of Scream City 2.]

AM: The sleeve was so stunning, that I am convinced that at least fifty percent of the people who bought that album, bought it because of the sleeve. Because they saw the sleeve and said "I don't know what's in it but I've got to own that".

The dilemma of course was that there are things that you don't know about when you're a kid in a band little two-word phrases "packaging deduction". We realised some where down the line, that we were losing money hand over fist because the royalties we were on were peanuts and the packaging deduction was killing us.

So it went through several variations of colour and then into a simple sleeve. Because somebody pointed out not to dissimilar New Order's Blue Monday that for everyone we were selling, we were losing money.

JC: Between one and ten pence, depending on who you believe. It didn't ever get as bad as that did it?

AM: I don't know what it was, because it wasn't a single but we definitely weren't making any money out of it.

AM: I still think to this day that of the first five album sleeves he did, probably the first and the fourth "Dazzle Ships", maybe I'm biased, but there up they're with the best sleeves he ever did. I noticed that when he was up for "The Iconic Designs of The Twentieth Century award he chose "Power Corruption and Lies".

JC: Which he has said is his personal favourite.

AM: Is it? Well he told me, he didn't think it was his best! "I've done better than that, but if they want one of mine, they can have this one. And if the only other sleeve in there is Peter Blake's Sgt. Pepper I can't really complain!

We have been lucky to work with Saville and of course there was another piece of fabulous chance. We did one record on Factory, lost touch with them, signed to Dindisc, and lo and behold, completely independently Peter Saville goes to London gets the job for Dindisc Records. So there we are, we've got Saville again.

JC: Saville recently gave a talk at his 'Estate' exhibition in Zürich2, during which he talked at length about Dazzle Ships. He called the whole Dazzle Ships story "a sharing of enthusiasm for the culture of the Twentieth Century".

AM: Peter would say that wouldn't he!

JC: But I think that's quite a nice way of describing it, because of its historical significance of the title and the artwork. It was also quite significant that he chose to elaborate so much about battleships. I also think it's a fantastic cover.

AM: And it also got expanded into a stage set, which was the nearest you'd see on a eighties pop group to a constructivist set. We built a 'Dazzle Ships' stage set, with things that moved with a screen and a map, flags and things.

I think 'Dazzle Ships' is possibly the best example of "the tail wagging the dog". It was actually Peter Saville who came to me and said "I have seen a Vorticist3 painting of 'Dazzle Ships in Birkenhead Dock' and I want to do a 'Dazzle sleeve'. Can you write a piece of music and possibly call the album 'Dazzle Ships'? To justify my decision to do the sleeve." It was completely the cart before the horse. I said "Yeah ok, What the fuck is a 'Dazzle Ship'?"

So it was Saville's desire to do a 'Dazzle Ships' sleeve that provoked me to do a song 'Dazzle Ships'. Then I said "We've got a track called 'Dazzle Ships', we'll call the album 'Dazzle Ships'; off you go. But yet again the day before he was supposed to deliver it, who ends up doing most of the work? Malcolm Garrett. Peter's pulling his hair out "oh what the hell am I gonna do!" and Malcolm says "it's just a fucking zig-zag camouflage like that!". Peter won't thank me for telling you that....

I think Peter was notoriously precious to the point where he would drive everybody working on something insane. I mean the cameo of him in 24 Hour Party People is a little unfair: the only three occasions you see him in the film he just walks in and they go "too late!". But it's not a really vast way from the truth!

JC - I think with New Order, Saville was generally being given a word or a title to work with and come up with an idea or even he was just working without anything at all, just preparing something which he would then show to the band. How would it normally work with OMD sleeves?

AM - It was a lot more from Peter. Obviously with the first album we had no control over whatsoever and he delivered an absolute gem. And then really from there on we were prepared to be led by Peter on the artwork because ever since 'Electricity', Peter had done such a great job that there just seemed no point in trying to suggest something. You always felt it would be secondary in quality so he was entirely left to his own devices.

I believe that the sleeves he put our records in were fantastically complementary. I think some of the single sleeves are stunning. 'Messages' is gorgeous. And 'Souvenir' when Peter said "what this sounds like is the middle eight in a French arthouse movie. When the boy has met the girl and there's a sequence where there's no dialogue, they're hanging round Paris and the soundtrack is Souvenir".

So he got that, the soiundtrack and created visual images in his head. I think it's actually a Düsseldorf street cafe from the very early Fifties which is exactly the kind of romantic idea of " European" which us northern kids would've had. And again, the two Joan of Arc sleeves ('Maid of Orléans' and 'Joan of Arc') he saw as the visual distillation of the music and he created absolutely wonderful sleeves.

The 'Junk Culture' sleeve was probably the one that was the least organised. The only thing that we definitely decided to do was that we finally wanted to move on from the serious, po-faced boys in thin ties, bank-clerk-meets-artistic look.

Basically we all decided to completely confound people's view of us and go from looking so boring it wasn't true. Because we were so serious about the music that we didn't want to look like anything especially since subsequently there was the advent of the New Romantics, the Spandaus, the Steve Stranges and all that lot.

We were like "we do not wish to be associated with all this namby-pamby fuckin' dressing up box crap" so we got more and more austere in white shirts and black ties and then eventually in 84 we decided to completely throw that out the window.

We combined with Peter to go completely the other way and go "rococo bonkers" and we all trooped off to Scott Crolla's shop just around the corner on Dover Street and all got kitted out in these bizarre things like shirts that looked like they were made out of your granny's curtain, tartan pants and eveything had to clash. Gone was the grey & white & it was loud as possible and clashing please.

We went to the Brighton Pavilion to shoot a photo session, in the most opulent interior we could possibly find in our loud shirts & the sleeve was going to be grand ornate gilt frames & possibly us standing in amongst them & flowers & everything. And it was a complete dog's dinner!

They were seldom used those photographs because they were just over the top. You couldn't see us because with all this opulence and the clothes and eveything it was "are there people in this!? Can I get my sunglasses out!?" It was too intense.

I think it was Peter working with the photographer Trevor Key, again probably at the eleventh hour who was saying "for fuck's sake, we've got to have a picture here and we don't like anything we've shot". I think it was probably Trevor who said to Peter "here, you see we've got this idea of sticking the flowers on this glass with the frames and everything behind them. The flowers on the glass, out of focus, look quite cool. What about this for an image? So again, it was like two o'clock in the morning, last shot, desperate measures. Of fuck it the flowers out of focus look quite cool. We'll have them sod the rest!

JC: I hadn't really thought of this, but the Junk Culture sleeve could perhaps be seen as a early test for Saville's later work on New Order's Technique or True Faith, that kind of dichromat era around the late Eighties.

AM: I don't think they treated it. But I think that the colour of the flowers suggested that they would start going into that area where they would really start cranking and screwing with the colours. Because obviously he distilled it then, taking very traditional images and screwing the colours to be ultra modern and bright and that juxtaposition was what made the strength of the idea. The New Order cherubs came from Saville, cause I used to love going round to his flat where he always had the most groovy furniture. I remember his Alvar Aalto bent wood furniture. I was really into Modernism and I remember going round one day and he had this friggin' rococo seat in the window, all gold and gilt and carved and I was like "What the fuck is that?". And he said "Oh this is my new thing now. I'm getting out of Modernism now." I thought he'd lost it. I thought he'd turned into a sixty-five-year-old over night. But of course he took all those images, he gave us the 'Junk Culture' sleeve. But then he modernised that kind of rococo barminess by the colour saturation and all that work you've just talked about.

JC: Was it The Apartment in Mayfair that you were talking about?

AM: No, it was his basement flat in Holland Park. On one trip to his flat, he played me Blue Monday for the first time and that's when I just thought fucking hell, New Order are trying to rip us off. They've got big blocks of choir sounds and drum machines! What's going on here! Where's all the gothic gone?

AM: I must admit, I'm going full circle, I'm re-living my youth and becoming an artist in-inverted commas again. After years of losing the plot, and just trying to write songs like a craftsman, I'm actually indulging at the moment that one of the things that were hoping to do with the comeback of OMD is an installation piece with Peter Saville.

The starting point was Stanlow, but we're going to do several pieces and I'm scouting sites now and looking at the North Hoyle Bank Turbines off the Flint coast, and electric mountain in Snowdonia where they pump water through caverns to generate power and Stanlow Oil Refinery. It's been great, I feel like a kid again. I've been doing a piece of music for the North Hoyle Bank, and just sitting there doing these bits of music, looking at pictures like we did for Sealand and Stanlow. It's really been like going back full circle, twenty-five, twenty-six years ago.

JC: I wanted to just take you back to 'Architecture and Morality' which I think for most people is the quintessential OMD album. A lot of people would either say this is a great experimental album with some great pop tunes or a pop classic with some moody electronic stuff. Which way did you conceive it at the time?

AM: There was no grand plan, vision or overview. To us at the time it seemed a natural, largely unconscious move forward. I think that the first album we did was very much 'Garage Punk Electric', very simple songs that we've been writing since we were sixteen. The second album I think was definitely was Joy Division influenced gothic, a lot of darkness and the sleeve captured that. The third one was the natural progression.

We went over there, but now were some where in the middle, moving forward. It combines several elements. There was the subject matter which was fascinating, in particular there was the two Joan of Arcs, the Gregorian chants on the title track, which were somewhat accidental things we scooped up on our journey the previous year because we'd been in France in Rouen and Orleans and people had been saying "Oh you're doing the Joan of Arc Tour of France".

I've always never seen things in black and white, I always see them in grey. So I've always been fascinated by people who've had an absolute strong definite idea, so I've always been drawn to religious themes or warfare themes. I find it hard to generate that certainty that people derive from either religious conviction or moral or national conviction from fighting a war. I'd find it hard to commit myself that completely.

So it had this sort of pseudo-religious sound which was helped by the sampling of Gregorian chants and the arrival of the Mellotron so you could finally play strings and choirs. The crazy thing is from the outside it may have looked like an incredibly clever balancing act, and maybe it was, but it wasn't a conscious.

Carol Wilson who ran Dindisc used to be driven to absolute distraction by us and her favourite phrase was "Do you two want to make your mind up whether you want to be Joy Division or Abba! Cause I can't work out what you're on about!". So that's it, it was one of those things. What was the most important track on that album? They're all our babies on there and we don't love any one anymore than any of the others.

It seems preposterous now, especially in this day and age when you're either ambient or hardcore or rock or electronic. You're pigeonholed. You've got to fit the category.

But here is an album which had three Top Five singles on it, sold two-and-a-half million and yet it's got a title track that's like concrete music, it's got a seven-and-a-half-minute ambient track with six lines of vocal in it about a place called Sealand. It just made sense to us.

We could quite happily go from Souvenir to architecture and morality. From 'Joan of Arc' to 'Sealand'. And if it confused people when it came out, great. The sense of achievement and pride of having an album toward the top of the charts, that so confounded the boundaries of what would normally be perceived as pop music was great. So it wasn't a pop record with some weirdness thrown in. It wasn't an ambient with some pop songs thrown on to sell it. All of it was done because we liked all of it. It all made sense to us. And it made sense to at least two-and-a-half million people.

JC: For me, cos I was at school when it came out, it was very much on one hand youth club disco because of the pop songs being played then and then it was getting the album, going home and playing it and thinking "oh wow!". For a young teenager it was quite a revelatory experience. And it's probably why for a lot of people around my age it's a very important album.

AM: I'm very proud of that! But if you analyse 'Joan of Arc' and 'Maid of Orléans' they were fucking weird! It wasn't "ooh baby, I love you! I hope you love me! Scooby dooby doo." For a start, none of them actually had a repeated sung chorus. The melody was the chorus and Paul or I was singing the verse. 'Joan of Arc' is actually an ambient gothic twelve bar blues that just repeats itself, then has a middle eight and then repeats to fade.

JC: You don't see much of that these days with the possible exception of Radiohead or U2 where a traditional song structure isn't followed.

JC: What do you think of modern day electronica on labels like Warp or City Centre Offices people like Aphex Twin or Miwon?

AM: I'll be honest with you John, I don't spend a lot of time listening to underground electronica music. It might seem to be a sad admission to make but it's kind of like "I did my bit for the cultural revolution about twenty-five years ago and I moved on from there, for better or for worse".

I'm not a sixteen-year-old now in his bedroom listening to John Peel saving his pocket money to go out buying German imports. I kind of know who I am now, when I was being influenced by people when I was a teenager I was inventing myself as teenagers do and music is one of the was that you create or discover your identity. I was one of those kids who was looking for it adopting it and, with Paul Humphreys turning it into something that became our own.

So there's stuff I hear that I quite like but I sometimes feel like "somebody did that before, so why am I listening to it again". We were never completely musique concrète, there was always an element of melody and charm and beauty and I don't get off on listening to something purely for the intellectual pursuit.

I can listen to something once and say ok I got that idea that's interesting, now give me a reason to listen to it a second time…I mean I like of Aphex Twin and it's kind of interesting to see that retro eighties music is making a come back. I have mixed feelings about it: On the one hand I'm delighted what we did twenty five years ago is now acceptable.

JC: They're probably using some of the instruments you used then!

AM: It's nice to been seen now as having a place in the cultural pantheon…

JC: So OMD are getting back together again, you're doing a tour where you'll be playing 'Architecture and Morality' and there's talk of a new album. How did all this come about – would you like to explain the story of how OMD got back together?

AM: It's started really in the middle of last year. Out of the blue we were asked to do a German TV show; it was a bit like one of those channel four count down like the top 100 bands ever. They were doing the top selling bands in Germany in the nineteen eighties.

We were in the top fifty and they asked of if we would like to do the show. I phoned up Paul Humphreys and said do you want to do a TV show for a laugh. He said yes, Malcolm our drummer also came with us, Martin couldn't make it because he had other plans. We went and it was such a laugh, it was great, we enjoyed it.

Twenty-five German fans turned up at our hotel asking for autographs because there is a pretty active OMD German website. So we got talking and it snowballed into us deciding that we may want to do something again. Paul asked me about five or six years ago but I was busy with other things like Atomic Kitten at that time. Now, it's like nine years since I stopped doing OMD.

At the time I was really banging my head against the wall. I was seen as being in a out of date Eighties synth-pop band and it was in the middle of Brit pop, and it was like "Forget it". But now there's a different perception. I've spent the last nine years working with different people and I felt like doing something for myself again. And Paul said he was interested and so did the other guys.

We've got some concerts booked for March 2007 where we are going to play 'Architecture and Morality' in its entirety. Paul and I are doing some gigs in Germany with an Orchestra. It's a thing they do every year. It's mixed classical rock called Nokia Nights At The Proms. And then hopefully in the year we've got several possibilities, were hoping we've got a fifteen date tour of Europe and possibly America.

Were hoping if that goes well, we might do some festivals. Paul and I are also meeting the Chief Executive of the Philharmonic Orchestra, who expressed some interest in doing some gigs next year. And we've also got this installation idea with Saville, so there's a lot of stuff coming along. If all of this comes together, we build upon our legacy and polish our brand name, and put ourselves back into the market and people respond positively, we would like to release a record. Right now I don't think people are waiting with bated breath for another OMD album, but if we come back and do this right and remind people of what we used to do, not have people think about us as some Synth band who had a few hits.

But it would be nice to kind of remind people where we came from: 'Architecture and Morality', the Arts, The Factory, and Peter Saville" That's where we started. That's our history. We did some pretty radical, yet successful stuff. Also, this Autumn is twenty-five years since 'Architecture and Morality' was released.

JC: So you wouldn't start recording something until you've done some live dates?

AM: We got a few bits of ideas lying around, some quite interesting ideas. The dilemma at the moment is that Paul Humphreys has said that he would like to do OMD, but he does have another project which is himself and Claudia Brücken (ex-Propaganda) in a band called One Two. He wants to complete that record and tour it. That's his primary band, but he would like to do OMD from time to time.

I'm not going to do it 365 days a year and my kids are still fairly young. If Martin Cooper comes along, his kids are even younger. So there's a lot of possibilities, it's just were all trying to juggle our time schedules.

JC: And will Peter Saville be doing a new sleeve for the new album?

AM: Yes, Peter has said that he'll do the sleeve, but the installation will probably see the light of day before the album. We would like to see it turned into an actual item, a combined audio-visual product, essentially a DVD that we would hopefully have in the installation project around giant screens with big surround sound music playing; so it'll be a complete audio-visual experience.

References

1 - László Moholy-Nagy. Wikipedia, Albers and Moholy-Nagy: From the Bauhaus to the New World, Tate Modern, London.

2 Peter Saville, Estate. Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zürich, Switzerland; 11 November 2005 - 8 January 2006; www.migrosmuseum.ch

3 Vorticism was a short lived British avant-garde art movement which drew heavily on Cubism and Futurism, and was founded by the artist and writer Wyndham Lewis in 1914. However the movement quickly petered out after the outbreak of the First World War, as did its celebrated journal Blast.

--

Many thanks to Andy McCluskey. Thanks also to Peter Saville, Tom Skipp and Ben Kelly for the 1980 tour stage design "blueprint" [see above right].

<-- |

Haçienda Classics by moist |

The Gig That Drives Me Mad by David Nolan |

--> |

Issue 2 index

- 1986: The 10th Summer around the Haçienda – goodbye punk, hello hedonism by Gonnie Rietveld

- Consumerism and Its Discontents: The Mis-selling of the Tenth Summer by Steven Hankinson

- The Haçienda Classics by moist

- Andy McCluskey by John Cooper

- The Gig That Drives Me Mad by David Nolan

- A Trip To The Seaside Parts 1 & 2 by John Cooper

- Cath Carroll by Mike Stein

- Giving Alvar Aalto to the Kids by Andrew James