Publications > Scream City > Scream City Issue #5 > Shadowplayers: The Rise and Fall of Factory Records by James Nice

Shadowplayers: The Rise and Fall of Factory Records

by James Nice

by James Nice

This extract from the new book by James Nice on Factory Records (published by Aurum Press, June 2010) deals with the opening of The Factory at the Russell Club in Hulme in May and June 1978.

On 9 May 1978 Wilson again wrote to Gretton to repeat that he 'adored' An Ideal For Living, and asked if Joy Division might be interested in playing at a new Manchester venue. Elaborating further, Wilson explained that 'the band I am involved with are promoting a new venue at the Russell Club.' Here, at last, The Durutti Column would be unveiled to the public. As well as launching their 'new psychedelic' proteges, in promoting a new wave club night Wilson and Erasmus also hoped to fill a gap in the market following the temporary closure of Rafters, and the demise of the Electric Circus. In this new endeavour the pair were assisted by Roger Eagle, a veteran of the legendary Twisted Wheel and now booking gigs at key Liverpool venue Eric's. Indeed the new Manchester club took the form of a reciprocal agreement, and was initially written up in the press as an outlet for 'wayward sounds and noises inspired by the ideals of Tony Wilson and Roger Eagle.' The venue itself was located by Erasmus, and sat in the shadow of the grim concrete high-rise crescents of Hulme, artlessly constructed a decade earlier. 'We had a group, we needed a place to play,' wrote Wilson. 'Alan had been checking the Russell Club, a West Indian night-spot on Royce Road in Hulme, where his dad used to take him. The Russell was a big, black room, low ceiling rising over a rudimentary dance floor in the centre, and a fair-enough stage diagonally cutting the far corner. Peeling wooden stools and tables, the bisexual perfume of stale beer and dope smoke.' Erasmus and Wilson approached colourful Russell Club leaseholder Don Tonay and booked four Friday nights in May and June, electing to re-badge what was widely known as a Caribbean club as The Factory. Then, as now, the suspicion remains that the Factory name was adopted in overt homage to the studio run by Andy Warhol between 1962 and 1968, with Durutti Column as Wilson's very own Velvet Underground.

However, this retrograde charge was always strenuously denied. 'With my background in radical art,' claimed Wilson, 'you would have thought that it would have occurred to me that the name Factory and Warhol was a wonderful thing. In fact it was nothing to do with that. Erasmus saw a sign somewhere saying, factory closing and he thought we'd call it the Factory, and have a Factory opening.' In a rare public statement, Erasmus told much the same story. 'I was driving down a road and there was a big sign saying, "Factory For Sale" standing out in neon. And I thought, "Factory, that's the name", because a factory was a place where people work and create things, and I thought to myself, these are workers who are also musicians and they'll be creative.

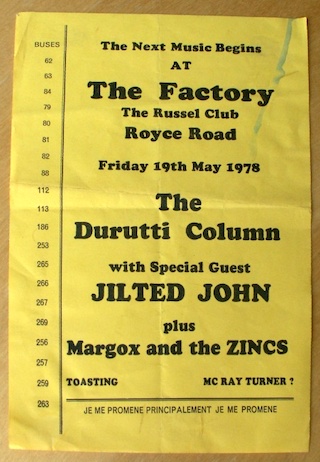

Factory was nothing to do with Andy Warhol because I didn't know at that time that Warhol had this building in New York called the Factory.' Whatever the truth, the exploding plastic inevitable convened by Wilson, Erasmus and Eagle offered a radical but smart programme of provincial post-punk talent, designed to position the as-yet untried Durutti Column at the centre of the new movement of Northern Modern. The first Factory event, on 19 May, showcased Durutti and coming hitmaker Jilted John, as well as Margox and the Zinc, a Liverpool 14 15 group fronted by actress Margi Clarke, then a regular contributor to What's On. With entrance costing just seventy-nine pence the first Factory night was well attended, although M24J and 'the next music' earned just one review in the national music press.

Stringing for Sounds, New Manchester Review writer Ian Wood observed that 'the Warholian name of this enterprise must seem like something of an enormous joke to the local residents of Hulme, Manchester's disastrous answer to Stalinist architecture, and what the regular clientele of the Russell Club think of the whole affair can only be guessed at, since the place normally serves up a mixture of roots reggae and US soul to a largely black local audience. The Factory is the dreamchild of one-time presenter of So It Goes, Tony Wilson. As one who enjoyed that show, it must be said that one of its consequences was to imbue all manner of upcoming and little known acts with a sort of jiveass fashionability for the coffee table set. So it comes as no surprise to find The Factory packed out by not merely half the musicians in town, but also a fleet-load of media people, semi-fashionable figures and known hustlers, hairdressers and even, according to the Word, hoards of A&R men. This may all be quite irrelevant, but it does provide a pointer for the reason why the bands on met rather less enthusiasm than the reggae toasters and disco between the sets, doing the ethnic hustle doubtless being a whole lot more credibility-inducing than actually trying to work out where a bunch of completely unknown new bands are going.'

Wood missed Jilted John, and poured scorn on the hopeful notion that Margox might yet become 'Kirby's answer to Patti Smith.' As for the main event: 'Durutti Column were making their debut this evening in the belief that agit-prop psychedelia is the next big thing. The Column have taken the title of a revolutionary group, put out posters with entirely meaningless cartoons in French and handbills with the message "White Liberation". As Tony Bowers, late of the Albertos, is the group's bass player, one is tempted to think all this some enormously funny joke. Unfortunately this doesn't seem to be the case. The only humour in the whole set occurs when they dedicate a number called Police State to one Anderton, Manchester's God-fearing man in blue. Otherwise they sounded much like Generation X, with the addition of Bower's copyrighted silly walks, though their guitarist [Vini Reilly] was interesting with an odd, angular, surreal style. In fairness, everyone else thought they were very impressive. Perhaps they were, perhaps I was reacting negatively due to the oppressively fashionable vibe in the club?'

Back at the office of New Manchester Review, Wood spoke more freely, resulting in more caustic jibes aimed squarely at Wilson. Declining to write up the first Factory night in detail, Steve Forster sniped: 'My informants tell me that "the Didsbury set" were out in full force for the opening night of Tony Wilson's "Factory" at the Russell Club on Friday 19 May. Not having been there I cannot comment on the night but colleagues tell me that Durutti Column were, ahem, "a load of wank". Needless to say it would be churlish to suggest that plugs for The Factory on Mr Wilson's What's On programme were in any way less than fair.' The second Factory happening, on 26 May, offered Big In Japan, Manicured Noise and The Germs, as well as more toasting and reggae between sets. Another Liverpool group dispatched east by Roger Eagle, Big In Japan offered shambolic, cartoonish new wave performance art, populated by a host of future notables including Jayne Casey, Ian Broudie, Holly Johnson and also Bill Drummond, later a founder of Zoo Records. Highly regarded by many, Manicured Noise dispensed spiky, angular, experimental jazz-punk and took their name from a Buzzcocks flyer designed by Linder.

Early Noise members included singer Owen Gavin and guitarist Jeff Noon, although the group would soon be transformed by the arrival of Londoner Steve Walsh, who had previously played in hypothetical punk supergroup Flowers of Romance, and boasted little or no local allegiance.

The last two Factory Fridays fell on 2 and 9 June. The first of these again showcased The Durutti Column, this time matched with FC Domestos and Cabaret Voltaire.

Yet to release a record, Cabaret Voltaire were a resolutely experimental electronic trio from Sheffield comprising Stephen Mallinder, Chris Watson and Richard H Kirk. A tape submitted to New Hormones had earned them a London support slot with Buzzcocks at the Lyceum in March, followed by a feature in Sounds in April, written by Jon Savage. Chris Watson recalls: 'We got invited over to play at the Factory night in a West Indian club in Hulme. That was just great. At the time Factory just had it for one Friday night each month, and so there were all the elements there of what it was like the rest of the time. You could get Red Stripe, and these fantastic goat pasties.

It just had a brilliant atmosphere, and because it was a West Indian club they also had a great sound system.' The New Manchester Review begged to differ, but at least had learned to love The Durutti Column. 'The venue was great,' enthused Paul Miller, 'but the sound system is crap and the bands suffer for this.

Cabaret Voltaire were... different. However after twenty minutes of distorted vocals and a very poor light show they started to become slightly monotonous. The second band, FC Domestos, were obliterated by the PA. Next were three reggae toasters with their overdubbed dub who went down well with the mainly white punters.

Meanwhile Tony Wilson walked around and generally enjoyed being the centre of attention. The evening climaxed with The Durutti Column. They play psychedelic punk with a strong reggae rhythm and their classy pedigree – the Albertos, Nosebleeds and Fast Breeder – creates a lethal line-up, with strong songs that belt along at cracking pace. Destined for great things as the latest Manchester band, they should have no trouble securing a record contract in the near future.' The final Factory night on 9 June paired Joy Division with The Tiller Boys, an experimental loop and Krautrock-informed trio featuring Eric Random, Francis Cookson and moonlighting Buzzcock Pete Shelley. Paul Morley attended, noting that 'there were a few more people in the club than on the stage, but not many. In my memory, this is when and where Joy Division became the Joy Division you would recognize as Joy Division. Joy Division assaulted our senses that night. Ian Curtis quite easily spiraled off the stage into our midst. The music seemed to lift him up and fling him about, as if he was possessed by its power. He was being carried somewhere.' Morley also rated The Tiller Boys, who stacked chairs across the front of the stage to obscure the view, then joined the queue at the bar while loops took care of the music. 'A visionary alternative to support groups and DJs.'

The first four Factory nights were promoted - at least in theory - by means of a now iconic poster designed by student novice Peter Saville. Born in 1955 and raised in a middle-class household in Hale, Saville was about to graduate in graphic design from Manchester Polytechnic, where his contemporaries included Linder and Malcolm Garrett, the latter a school friend of Saville and already applying dayglo constructivism to Buzzcocks. 'Malcolm had a copy of Herbert Spencer's Pioneers of Modern Typography,' recalls Saville. 'The one chapter that he hadn't reinterpreted in his own work was the cool, disciplined "New Typography" of Jan Tschichold, and its subtlety appealed to me. I found a parallel in it for the new wave that was evolving out of punk. In this obscure byway of graphic design history, as it seemed at the time, I saw a look for the new, cold mood 17 of 1977-78.' Thus far, his only commission had been a broadsheet for a local audio firm, Amek. Frustrated, Saville buttonholed Wilson at a concert and offered his services as a general designer. 'I was desperate for work other than college things, and jealous of Malcolm working on Buzzcocks covers.

So I approached Tony on hearing of the Factory club through Richard Boon.' The pair arranged to meet in the canteen at Granada, a regular venue for summits with Wilson. In loquacious sophisticate Saville, the pseudo-Situationist Durutti co-manager perhaps hoped to procure his own Jamie Reid. 'The crucial thing about graphic design is that you have to impart a message, information,' Saville concludes. 'If that means simply putting a name on a piece of paper in the right type at the right size, then that's what you do. I showed him the Tschichold book, and he liked the ideas.

Although Tony's sensibilities were always literary rather than visual. He would never have opened a hip clothes shop like Malcolm McLaren.' Tschichold aside, appropriation became almost an article of faith for Saville. In part, this postmodern creative approach was inspired by Kraftwerk, whose 1974 album Autobahn was the first record purchased by Saville with his own money. Having long admired the 'found' motorway sign on the cover, he now based the first Factory club poster on a found object of his own: an industrial safety sign displayed at Manchester Poly, warning workers to use hearing protection. 'Practically speaking, the inspiration for the first poster came from a sign I saw every day on a workshop door at college,' says Saville. 'The charm of this sign came to my mind quite quickly, and I was keen to distance the identity and the event from the notions of pop and Sixties culture.

I had reservations about the Factory name because of the Warhol connotations. So I became quite determined to use the sign, and to suggest the industrial context for Factory, and its place in the North-West. I had to resort to removing the sign from the door one evening.' Despite receiving a fee of £20 for the striking yellow, black and white design numbered Fac 1 by Wilson, Saville delivered the poster only after the first two shows took place in May. Unlike the perplexing cowboys poster intended to promote The Durutti Column, none were fixed to walls in public places. 'It probably was quite late,' he allows. 'Most of what I did usually appeared quite late.'

Copyright James Nice/Aurum Press 2010

--

Q&A with James Nice

The Shadowplayers DVD came out in 2006. Why did the book take so long?

Partly because it covers the entire Factory story from 1978 to 1992, rather than just the first five years. I did think about doing a book version just after I did the DVD, along the same lines as Dave Cavanagh's excellent Creation Records history (2000), but so far as I recall Alan McGee was quite dismissive of that, and said it was an accountant's version of the Creation story. I fancied Wilson might say the same about a Factory book written by me, but when Tony died in 2007 it liberated the history a bit. I don't mean that to sound as awful as it does.

How did you find a publisher?

Thank Fac 196. I got in touch with Nicholas Blincoe to ask him some questions about the Meat Mouth single, and he asked who the publisher was, did I have an agent, and so forth. Nick kindly hooked me up with his agency, and they struck a deal with Aurum Press. They've been great. It's a pretty long book, over 200,000 words, but they didn't insist on any cuts. Plus it has a proper index, source notes, plate section, etc. I hate it these days when you buy a non-fiction book and there's no index, or quote attribution. Jon Savage and Simon Reynolds were also very generous when it came to endorsements.

Is it all new interviews? Half and half, which is entirely deliberate.

My attitude towards evidence and oral history was coloured by my experience as a newly qualified lawyer on the Bloody Sunday Enquiry, back in 1998. I was part of a large team taking witness statements from people who'd been involved in dramatic events 26 years earlier. That really gave me an insight into the different ways memories evolve. It's very similar interviewing people about Factory. Some people recall things with absolute clarity. Others have poor memories. Some memories prove to be false, either by accident or design. Some people tend towards being anecdotal, or else unwittingly fill gaps in their own memory through press reports or footage.

So I thought it was important and necessary to quote – at length – what people said at the time, as well as what they say now. Usually it's quite different.

Often if you read your own old diary entries, you don't recognise that person - but that's who you were then. Add to that the complication that groups like New Order and A Certain Ratio didn't really speak to the press between 1980 and 1983.

Hindsight usually provides a more considered perspective, but it is a filter, and sometimes you have to remove it. Bit like the difference between Marlboro Lights and Capstan Full Strength.

Such as?

Well, anything Wilson said. He's on record as preferring myth to fact. That book of his, 24 Hour Party People, was horribly slapdash, sort of Carry On Factory. If you're after specific incidents, even at quite a late stage Martin Moscrop was adamant that Ratio's first trip to New York in September 1980 wasn't with New Order.

It was. Another one that springs to mind is in the DVD where Peter Hook is talking about The Factory, saying that he and Bernard had already been there when it was a heavy metal club. I only realised later than he was confusing The Factory with the Electric Circus. Obviously my own life hasn't been quite as exciting or eventful as theirs, and you find yourself wondering how errors occur. But I got a taste of my own medicine when I wrote the postscript, and thought back to my own visit to the Charles Street office in 1992. I think my meeting with Tony Wilson and Phil Saxe was in the boardroom around the floating table, but I had to double check with someone else – who also didn't remember. That brought it home to me how much I was asking of people to remember particular incidents at particular gigs 30 years earlier, and so on.

The postscript is the only part of the book where I placed myself in the text, by the way. I didn't want to look a twit by trying to write myself into the Factory story.

What about using quotes from reviews?

Album and single reviews are pretty subjective, hit and miss, but in my opinion live reviews are usually a valid eyewitness account. Paul Morley was unerringly accurate across the board. It's worth pointing out that music journalism two decades ago was very different. Back then, it was quite common for artists (and labels) to get slated for editorial reasons, or ideology, or simply a cheap laugh. Now you tend not to see really negative reviews. If a magazine doesn't like something, they simply ignore it. Not sure if that's better or worse.

Everything in The Culture is far more calculated these days.

To what extent did New Order open up to you?

I think there is probably more in the book than some people would like to be in the public domain – or at least put in the public domain again. I think the majority view with New Order is that you don't air dirty linen in public. But it goes without saying that Joy Division/New Order are central to the whole Factory story, because they were in effect equity partners in the label. Really Shadowplayers is three books in one. It's the story of Factory itself, the personal relationships between the key players, and also the story of The Haçienda. There's maybe a dozen people who are at the heart of the story: the five original directors (Wilson, Erasmus, Saville, Hannett and Gretton), also Mike Pickering, and then the members of Joy Division/New Order.

Steve Morris and Peter Hook did interviews for the book, and Gillian Gilbert confirmed a few details. Obviously Rob Gretton died in 1999, but his partner Lesley Gilbert was very helpful indeed, and I also interviewed Rebecca Boulton. I did have a list of questions for Bernard Sumner, but eventually all the answers emerged from other interviews. He's very frank when he wants to be.

I was surprised to see Alan Erasmus quoted...

Alan is famously reticent, and elusive, but we spoke quite a bit on phone, and in the end he decided to go on the record to talk about his relationship with Tony, and their reconciliation when Tony was ill. Prior to that I sent him a copy of the consultation draft, and made the mistake of warning him I was on my way round to drop it off. So of course he'd slipped out by the time I arrived. Alan said he'd pull me up on any 'glaring errors' so I assume there are none. Hope, anyway. Despite the fact that Alan and Rob Gretton rarely gave interviews, and were pretty inscrutable to outsiders, their voices are heard a lot in the book.

Peter Saville gave over a lot of time to Shadowplayers, and his memory and perspective is very acute.

Does the fact that quite a few of these artists have re-releases on your own label, LTM, mean that you pulled punches?

No, but it certainly made me fact check as much as I possibly could, which is the right thing to do as well as being a defensive measure. Maybe I hid behind a negative review quote once or twice. But I think I've always been quite robust when writing earlier sleevenotes for CDs. Probably too robust for some groups!

Did Factory influence LTM?

As a business, not at all. I absorbed far more from Michael Duval and Crépuscule in terms of what to do with a label, and what not to do. Before I moved to Brussels in 1987 I was particularly keen on Section 25, Crispy Ambulance, Minny Pops and The Names, who were all very Benelux. Also Tuxedomoon. Besides the music, I think the main thing that struck me about Factory at the time were the sleeves and design aesthetic. I still think that a good sleeve is as important as the music on the record. I hardly ever argue with bands about their music, but I'm happy to lock horns if I think a sleeve idea is below par. You can judge a book by its cover.

Speaking of which, how did you settle on the Shadowplayers jacket design?

That was actually quite hard. The cover design couldn't focus on any one particular individual or group, and although Fac 1 and Fac 2 are kind of default identities for Factory as a whole, those designs and colour schemes have already been used and abused for other book jackets, box sets and so forth. Using the 1984 building / roof / smoke logo was always the lead idea, and we ended up basing the layout and scaling on a Factory business card. The die cut adds 'ideological bling' in the words of Peter Saville, though actually it was Aurum's idea.

Peter possibly preferred foil blocking. And I guess I should point out that the 1984 logo was designed by Phill Pennington, who worked at PSA at the time.

Did you have to fight to include a lot of information on the smaller groups?

There was always a debate about the balance between specialist information and narrative drive, but no argument. It can be hard to break off for diversions about Kalima or Crépuscule, but the real Factory story is about all the personalities and events, not just Wilson, New Order, the Mondays and The Haçienda.

Otherwise you end up with a glorified glossy magazine article. That's also why I cover artists like Cabaret Voltaire, OMD and James throughout the book, even after they moved on from Factory. Especially OMD, because you could argue that their career begged big questions over whether New Order really needed to remain on Factory to retain creative control. At the time, Architecture and Morality outsold Power, Corruption and Lies tenfold.

Do you see Factory story as primarily about music or art?

I think Factory really was the post-punk Bauhaus, situated in Manchester rather than Weimar. It's genuinely that important. I'll put money on Tate Modern staging a major Factory retrospective at some point in next 25 years.

Where do you stand on whether Tony Wilson attended the first Pistols gig at the Lesser Free Trade Hall on 4 June 1976?

I think he must have been there, as Alan Hempsall recalls talking to him about a Kiss gig, and asking for his autograph.

Alan didn't go to the second Pistols show in July, and I very much doubt he made any of this up. I mean to say, chatting about Kiss and asking for an autograph! Here's a thing. Only a few years later, Kraftwerk emerged as a far more important musical influence than the Pistols, yet only Andy McCluskey of OMD seems to have seen them on their UK tour in 1975. No-one seems to fib about seeing Kraftwerk, so I think the whole 'I swear I was there' debate around the Pistols is maybe a little overcooked.

Anyway, it was easier to copy the Pistols with bass, drums and guitars. Technology made emulating Kraftwerk a rich man's game until the emergence of cheap technology around 1981/2.

Finally, what do you think Tony would have made of the book?

I think he would have dismissed it as an accountant's version of the Factory story.

Shadowplayers is published by Aurum Press and is available to buy from a variety of online bookstores.

<-- |

The Absence Of The Object Becomes A Presence You Can Feel by John Cooper |

The Distractions |

--> |

Issue 5 index

- A Factory Trip Around the World by Andrew James

- The Absence Of The Object Becomes A Presence You Can Feel by John Cooper

- Shadowplayers: The Rise and Fall of Factory Records by James Nice

- The Distractions by David Quantick

- Closer, Karamazov and K550 by Ian McCartney

- 33°52'38.29"E / 151°13'05.79"S by Matthew Robertson

- Our Man in Germany by John Cooper

- Factory Over America Part 1 by John Cooper

- Factory Over America Part 2 by John Cooper

- Looking From A Hilltop... at Lytham St Annes by David Nolan