Publications > Scream City > Scream City Issue #4 > Sample Minds: Before and After A Factory Sample by Andrew James

Sample Minds: Before and After A Factory Sample By Andrew James

When the fledgling Factory label scraped together the money for A Factory Sample in late 1978, they were following in the tradition of record companies large and small who, in the pre-MySpace age, used compilations of the labels' artists to market their imprint, to act as a sort of shop window, or a statement of intent.

Some, like Factory, did this at the outset of trading (such as Beserkley, with the cheekily-named Beserkley Chartbusters, the label's first release), others did it at regular intervals throughout the life of the label (e.g. Virgin, Island).

The best label samplers, to my mind at least, are those that encapsulate a label's ethos within their grooves. Of course, this presupposes that the label in question has an ethos beyond making money.

One of the first such compilations (i.e. that was effectively a snapshot of the label's mindset) was the Island Records sampler You Can All Join In released in 1969. While other labels had released compilations prior to this (notably CBS, whose The Rock Machine Turns You On was released in 1968), these compilations tended to showcase only a part of the output of large conglomerates with little coherent musical policy.

Motown, similarly, had begun its long-running Motown Chartbusters series in 1967, and while the music on these compilations in many ways reflected Berry Gordy's label's policies, they were first-and-foremost round-ups of Motown's hits (and in some ways the forerunners of the Now That's What I Call Music compilations), rather than an opportunity to showcase the undiscovered, the new and the plain weird alongside better-known acts.

You Can All Join In, then, was (a large part of) Island's A&R policy in the late sixties in microcosm. Featuring Traffic, John Martyn, Fairport Convention and Free, it documented label chief Chris Blackwell's then-obsession with pastoral blues, folk and rock.

It didn't feature the label's greatest hits, preferring to showcase album tracks and obscure recordings.

It also showcased popular artists (Traffic, Fairport Convention) in order to introduce audiences to newer ones (Wynder K. Frog, anyone?), a marketing tactic that was later emulated by other labels. But most important of all, you could detect the imprimatur of a tastemaker (in this case, presumably, Blackwell), curating the album from an artistic point of view, rather than a bean-counter compiling it from a financial perspective.

The fact that Island is widely regarded as one of the first independent labels, and was therefore trading for artistic reasons as much as financial ones, is important too.

The label sampler, then, became a tool with multiple purposes; for the punter, they were low-risk purchases featuring a variety of artists, usually curated by someone with a modicum of taste.

For the small independent labels and experimental major label offshoots that put them out, they were often financial lifelines (especially as artists frequently had to forego royalties on compilation tracks), as well as shop windows for the label's wares.

Buyers who bought Harvest's Picnic—A Breath of Fresh Air, for example, would have been left in no doubt as to the label's direction, namely progressive rock from the likes of Pink Floyd, Roy Harper and Kevin Ayers.

Similarly, Vertigo's Annual 1970 acted as a showcase for that label's A&R policy, i.e. prog, blues and proto-heavy metal from the likes of Uriah Heep, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath.

And if you liked one Vertigo artist, there was a good chance that you'd like others on the label, something that you couldn't necessarily assume about, say, Parlophone, Decca or Pye during the same period.

Usually, the cover art for these compilations tipped off the prospective buyer as to the content; You Can All Join In featured all the artists congregating on a windswept English hill, while Annual 1970's cover depicted a naked woman on a rocking horse in a purple field.

Meanwhile, some inkling of the relaxed and "free- spirited" sounds contained within the grooves of There Is Some Fun Going Forward, the sole label sampler put out by John Peel's Dandelion Records, can be inferred from its cover art, which featured Peel in the bath with a topless, nubile female.

What, then, can we infer about Factory's principles and musical direction from its first release?

That while the label's mainstay would be serious young men with guitars (Joy Division, The Durutti Column), it would also flirt with electronica (step forward, Cabaret Voltaire); that it wouldn't have a problem with non-exclusivity (the Cabs, again, recorded largely for Rough Trade rather than Factory prior to 1983); and that, in showcasing comedian John Dowie, the label would look beyond mere music in its mission to bring culture to the masses, a policy it continued by working with non-musicians as diverse as David Mach, William Burroughs, Bernard Manning, Ben Kelly, Fred Vermorel and Kathryn Bigelow during its 14 years of trading.

Above all, though, A Factory Sample's Peter Saville-designed sleeve foregrounds the label's emphasis on design, a particular concern of Factory throughout its brief but influential foray into the music business.

Factory, of course, weren't the only independent label putting out compilations. Island, Virgin, Vertigo, Impulse and even Polydor continued to release numerous label samplers prior to Factory's formation, many of them excellent, but the proliferation of labels from 1978 onwards engendered a concomitant increase in the number of label samplers released into the shops, or so it seemed.

The DIY gauntlet laid down by punk led to an explosion of small independents such as Y, Crass and Cherry Red, all of which put out samplers at regular intervals to introduce audiences to their artists, and to capitalise on rare successes by compiling new artists alongside their hitmakers.

Here, then, is a brief look at some of the more interesting label samplers that appeared during Factory's heyday...

It would be entirely reasonable to expect that, upon leaving university, the heir to the Mothercare fortune would knuckle down and get on with the important job of selling prams and baby-gros to Britain's mums-to-be. Michael Zilkha (for it is he) eschewed this obvious career path, opting instead to decamp to New York and write theatre reviews at The Village Voice, before teaming up with French expatriate Michel Esteban to found the short-lived but influential Ze label, which was good news for readers of The Face and other early-eighties hipsters.

Ze's early statement of intent was entitled Mutant Disco, a sampler that appeared in early 1981 to document the sounds coming out of downtown NYC, and which was housed in a day- glo sleeve that perfectly reflected the upbeat, waspish music it contained.

The LP featured tracks by Was (Not Was), Material and various configurations of Kid Creole and The Coconuts. During the labels' lifetime it would put out terrific and quirky material by similarly-minded artistes such as Lydia Lunch, Davitt Sigerson, and James Chance, most of whom deftly managed to straddle the line that demarcates the commercial from the avant-garde.

Indeed, it was Ze's genius that most of its financial successes (Kid Creole, Was (Not Was)) didn't alienate the critics, while its critical successes (Cristina, The Waitresses) could, in an alternate universe, have been worldwide smash hits.

The sampler was recently re-released by a resurrected Ze (now run solely by Esteban; Zilkha is too busy being a global energy mogul), and was expanded from its original 6 tracks to a CD-tastic 25 tracks. And while the re- release really gives you a wider view of the label (it includes tracks by Lizzy Mercier Descloux, Aural Exciters and Caroline Loeb), the original vinyl is a perfect distillation of what Ze was all about, namely knowing, literate funk with an ironic smirk, disco music with quotation marks around it.

In a similar vein to Factory, Stevo Pearce's Some Bizzare [sic] label was founded in part to document an emerging musical scene, one that Stevo had seen (or at least heard) at first hand in his guise as "futurist" DJ at London's Clarendon Hotel in Hammersmith.

Some Bizzare's stock-in- trade was cheap-sounding early electronics with a healthy dose of good old- fashioned sleaze. The imaginatively titled Some Bizzare Album was the label's first release, and is now rightly regarded as extremely prescient, not least because it documented some of the first recorded output of soon-to-be massive artists including Soft Cell, Blancmange, The The and Depeche Mode (the latter three quickly decamped to other labels, while Soft Cell remained).

The rest of the album is made up of the also-rans and never-weres of the early electronic scene, including B-Movie, Blah Blah Blah and Jell (the latter featuring Factory fellow traveller Eric Random).

Of most interest, however, is the track by Illustration, entitled Tidal Flow. One of the great lost bands of the era, Illustration were pencilled in as Some Bizzare's premiere act, and to this end recorded a single, Danceable, with Martin Hannett. Sadly, the single never saw the light of day, as Illustration split shortly after its recording.

Julia Adamson of Illustration later became Julia Nagle, a mainstay of The Fall for much of the 1990s, and latterly Julia has released Danceable as a downloadable single some twenty-seven years after its recording.

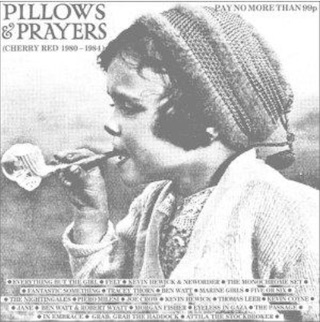

However, if you were tempted by the cover price, and if you were broad-minded enough, there was a good chance that you'd find something to enjoy, from the winsome tones of Everything But The Girl to the primitive electronica of Thomas Leer by way of spoken-word pieces from Quentin Crisp and Atilla The Stockbroker.

Despite its apparent patchwork quilt of musical styles, the album (which topped the independent charts for 19 weeks) hangs together brilliantly, and its diversity reflects perfectly the broad church that was (and is) Cherry Red, a label that runs the gamut from 1970s football songs to the Dead Kennedys via guitar troubadours such as the great (ex- Factory artiste) Kevin Hewick.

Though the choice of music on Pillows and Prayers is extremely catholic, the album somehow attains a coherence, the artists united by the innate good taste of label founders Iain McNay and Cherry Red A&R man Mike Alway, both of whom stamped their personalities all over the record. Alway went on to found the similarly eclectic El label under the auspices of Cherry Red.

Perhaps the sine qua non of indie samplers, and certainly the biggest- selling (largely by virtue of its 99p selling price, one suspects), Pillows and Prayers was a ragbag of contrasting styles and seemingly-mismatched artists.

Like Mutant Disco above, Pillows and Prayers has been repackaged for the digital age with numerous extra tracks and DVDs attached, but to really transport yourself back to the era when The Nightingales and the Marine Girls were the last word in indie-chic, you should really track this down on scratchy 99p vinyl. And listen to it in a damp bedsit. While drinking snakebite and blackcurrant.

The label had already been trading successfully for 4 years when it released the first Pay It All Back (five more samplers in the series appeared at various intervals over the next decade or so), and so this is less a manifesto than it is a snapshot of a work-in-progress.

In fact, it was a snapshot taken at a particularly interesting time, as On-U head honcho and in-house knob twiddler Adrian Sherwood was tiring of reggae (partly in revulsion at the senseless murder of Prince Far I in 1983) and turning instead to the sounds coming out of New York.

Thus, while the album contains straight-ahead dub tracks from the label's recent past by acts such as Singers & Players (the astonishing Bedward The Flying Preacher) and African Head Charge (Timbuktu Express), it also showcases newer electronic cuts by artists such as Mark Stewart (sans Maffia), The Circuit and Voice of Authority, (the latter two are essentially noms de plume for the usual On-U muso suspects).

Some label samplers, like Factory's, try and seduce the buyer with fancy packaging and beautiful graphic design. Of course, the money to pay the designer has to be factored in to the final selling price of the finished artefact.

The fact that the On-U Sound album Pay It All Back Vol. 1 retailed for a mere £1.49 upon its original release may explain why its cover looks like it was assembled by a GCSE student.

Actually that's probably not the reason; even full price On-U albums came packaged in similarly amateurish sleeves. If, however, you can look past the graphics and concentrate on the grooves, the LP offered up some terrific exclusive tracks and did a pretty good job of summarising the On-U modus operandi circa 1984.

Underlining the tougher, more electronic direction the label was to take for the next five years or so, the aforementioned acts are here assisted by Tom Silverman, head of the Tommy Boy label, avant- garde composer Steve Beresford, and Daniel Miller of Mute Records. Of course, it wouldn't be an On-U album without quirky samples, distortion, DJ voiceovers and cut-ups, all of which are present and correct.

"This LP is almost a gift," proclaimed the sleeve notes on the rear of the album, again referencing the low cover price. And while some (including this writer) may cavil at the sleeve design, only a churl would fail to receive the LP in the manner in which it was intended. Interestingly, as with most of these compilations, there is a Factory connection: On-U's sole break-out artist, Gary Clail, remixed Deadbeat by Peter Hook's Revenge in 1992 for the Manchester label.

Paul Morley's history with Factory is well-documented; from championing Joy Division more or less from their inception to appearing as a commentator and provocateur throughout the labels' life and beyond (the Palatine box set, the documentaries, the Urbis talks...).

It's tempting therefore, to view Morley's tenure as creative director at ZTT from 1983 to 1988 as Factory with a large budget; certainly the same maverick spirit of situationist pranks prevailed at ZTT, as did a frankly baffling cataloguing system that, like that of Factory, imbued events, jokes and ideas with the same significance as actual record releases. What ZTT did have over Factory (at least before 1987) were bona fide chart hits, not just records that occasionally grazed the top 30.

With money pouring in to the label from Frankie Goes To Hollywood and (to a lesser extent) Propaganda and the Art of Noise, Morley was able to indulge more avant-garde acts, and ZTT Sampled was an ideal forum in which to do so.

Alongside the obligatory demos and B-sides from ZTT's headline artists, the LP features offerings from Philip Glass-a-like composer Andrew Poppy (formerly of Crepuscule artists The Lost Jockey) and French torch singer Anne Pigalle. The most interesting new act on the LP, though, is another one of those bands-that-got- away, Instinct, made up of Simon Underwood (ex-Pop Group), and ex-Pigbag hands James Johnstone and Andrea Jaeger.

The band were (as with Illustration, above) being groomed for the big time, appearing at London's Ambassador's Theatre alongside other ZTT acts in a show compered by Morley, and recording a single (Sleepwalking) with producer Trevor Horn.

However, the group reportedly disagreed with Horn's ideas in the studio. Normally, in this instance, a record label might step in to mediate, or perhaps to appoint a new producer. Instinct, however, found themselves in the unfortunate situation of having their producer (i.e. Horn) own their label. Which led to the swift termination of their contract, and the non-appearance of Sleepwalking.

Thus the track that features on the sampler, Swamp Out, turned out to be Instinct's only recorded work, and it's our loss. Because Instinct were perfectly in tune with their times. Their music (punchy, shiny, clever) was, like that of Win or ABC, designed to appeal to the head as well as the heart. And they looked fantastic in an era when looks were all.

Sadly, this LP (along with their Grace Jones LP which appeared in the same year) was ZTT's conceptual high- water mark. Audiences were willing to indulge Paul Morley's caprices as long as the music was up to standard. But a below par second album from Frankie Goes To Hollywood and frankly rubbish material from later acts like Das Psych-Oh Rangers failed to endear the label to the record-buying public.

Morley left in 1988 to restart his media career, while ZTT got a second wind by signing acts like 808 State and Shades of Rhythm at the turn of the 90s, but wit Morley gone, its days as Factory's mainstream doppelganger were firmly behind it.

Catalogue numbers were simplified. The pranks stopped. The accountants reined in the excesses. Eventually it threw its progressive A&R policy out of the window, and today it's a very ordinary record company signing very ordinary acts like Shane McGowan and Lisa Stansfield. So track down ZTT Sampled if you can, and indulge in nostalgia for a time when pop could be subversive and commercial at the same time.

--

<-- |

FAC-2 Cabaret Voltaire by Michael Eastwood |

Scream City 4 |

--> |

Issue 4 index

- Tony Wilson by David Nolan

- FAC-2 Joy Division by Michael Eastwood

- FAC-2 The Durutti Column by Phil Cleaver

- FAC-2 Travel For Pleasure Alone by Colin Sharp

- FAC-2 Industrial Relations by Matthew Robertson

- FAC-2 John Dowie by Ian McCartney

- FAC-2 Cabaret Voltaire by Michael Eastwood

- Sample Minds: Before and After A Factory Sample by Andrew James